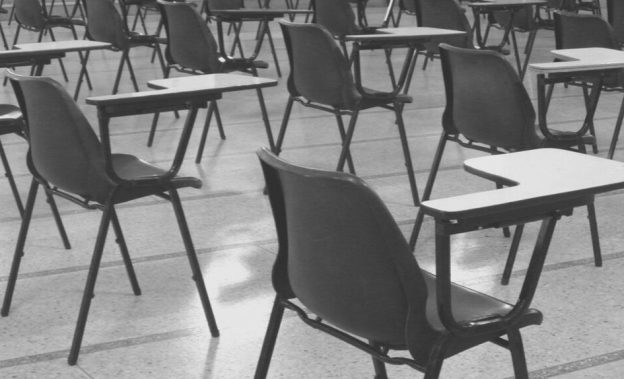

Sometimes, it’s the middle of the semester, sometimes right at the beginning, students like you disappear, leaving empty desks, incompletes, forgotten contracts.

Ruby Chen, your smiling face haunts me in the photo roster. I worry you lost someone: a brother, a sister, a mother. How long were your drowning in grief before we asked for your date of graduation? How long before your roommate knocks on your door? Were you left on some southern shore? Did the guard look up from your papers and say, not this time?

I worry that you found someone so callous, so cruel. How long before someone believes you, Ruby Chen? I wonder where you are if you are still with him, her, them. You are naked, dying on your bathroom floor, reaching out for something, anything. My overstimulated academic brain fixates. My email piles up at your doorstep like snow.

How sick were you this time, Ruby Chen? Chronic aching in your bones, no diagnoses, doctors everywhere, if you are lucky. How long will you be gone? Do you know, or are you still guessing yourself, always wondering, hoping, wishing, one moment from responding, one moment from trying again.

Academia will require you, as penance, to provide your sad story, so that it may be weighed against other sad stories to see if it is indeed sad enough, worthy of your debt to us. I don’t want to hear your story, because no matter how we failed you, we owe you nothing, for bringing you to this college town where there aren’t enough doctors, priests, or friends. We can only provide the salve of assignments to make it up to us, contracts to do better.

I sent email after email, but in the end, if you return, I hesitate to ask. I don’t want to hear your sad story, because if I hear your sad story it will become every sad story of every empty chair, every smiling face in the photo roster.

What did we do to you, as a college? When did we forget to believe you? When we choose not to forgive? Point to our institution policies like shackles, and say, not us?

Sometimes, as if by nothing, you return again. Sometimes meek, apologetic, but sometimes you return defiant, my emails answered with disrespect, rage bitter on your tongue. YOU. ARE. FINE. In the course evaluation you will point out all of my red marks, salt water poured on wounds from an institution uncertain if I can be trusted. There is often no explanation. But I would rather see your defiant face than 0, 0, 0, 0 growing across my course management system.

Ruby Chen, I will have to fail you.

But Ruby Chen, we have failed you.