I wrote this piece about a year and a half ago for the journal The Political Librarian. In the meantime the journal switched editors and it appears that the editor has stopped publishing the journal so I am uncertain if it would ever come out, so I am posting this here. I wrote this in April 2019. Hopefully it is helpful to others.

Introduction

Government is full of non-librarians. There are lawyers, doctors, teachers, factory linemen, farmers, and accountants. Librarianship’s core tenants of access, progressiveness, inclusion, and the public good make them excellent public officials. They have experience dealing with the public. They are excellent event planners. As an academic librarian, I myself have had plenty of experience speaking publicly, especially to groups of sleepy freshmen.

In 2018, more first-time candidates, women, and minorities ran for public office than ever before. In this paper, I will share my experience as a librarian successfully running for county council, ultimately knocking on over 2000 doors. I will chronicle why as an academic librarian I chose to run for public office, what librarians can bring to the table as politicians, and why more librarians should seek public office. With experience in public service, democratic participation, and systems thinking, librarians bring a vital set of skills to elected office as well as to the campaign trail. It is my hope that by telling my story I will encourage other librarians to run in similar representative numbers to that of other disciplines such as teachers and lawyers, as well as to challenge non-librarians to consider how these librarian skills contribute to society.

Why You Should Run

Back in 2017, I was sitting in a library conference program on eliminating late fees in public libraries. The research was all there: charging late fees was an unjust and oppressive practice, and most of the people in the presentation agreed. The question was whether libraries could convince their city and county councils. At the time I mused to myself, wouldn’t it be simpler if librarians were in those positions in the first place? In this era of fiscal responsibility, we need to make sure county, city, and district governments are full of people who understand the value of libraries, especially at a local level.

Certainly we can communicate that value, but the constant re-education of people is labor for librarians. We need people who understand the issues our communities from the beginning. Public librarians in particular are often on the front lines of the opioid crisis. When naloxone started to become readily available, librarians were some of the first people to get trained (Correal 2018). Librarians often work with our cities’ homeless populations. Children’s librarians know quite a bit about early childhood development. Librarians provide research help for entrepreneurs in the community. In these initiatives and others, librarians are often at the center of their communities.

Librarians should run because we think differently due to the nature of our work. When your whole job is thinking about how to help find and use information, you developed a systems-focused mindset. I think about things in terms of inputs and outputs, processes and outcomes. Even a small policy can have a large impact upon my users, and as a librarian I take that responsibility seriously. Librarians really do believe in the public good. We really believe that our profession is designed for the greater good and librarians are already public servants. We really want to do everything in our power to make the world better, and that includes getting out of our buildings and into the community. What better way to serve your community than to serve on your city council?

Librarians have research super powers that come in handy on the campaign trail as well. Candidates have to dig through meeting minutes, task force reports, newspaper articles, and best practice presentations to find polices that will purposefully help the community. On the campaign trail, I often advised other candidates how to do advanced searches on newspaper archives, how to subscribe to Google Alerts, and how to find government reports on pesky websites.

Reference interview training also comes in handy when talking to people at their doors. There’s a misconception that people don’t care about local elections. People do care quite a bit, but they don’t have the language for how to talk about what they need. I found that often a conversation that started about trash bins often ended in discussing best practices for sustainability. A conversation about roads leads to talking about how to make public comment on transportation commission meeting. Does that mean that I always had the answer to their question? Does a librarian ever have the answer to every question that comes across the reference desk? Of course not, but we know where you might look, how you might think about the problem. Years of working reference desk really comes in handy.

Effects of my Run

I’m a 32-year old professor and librarian located in Indiana. In 2018 I ran against a two-term 75-year old incumbent who was also a retired school principal for a district position on the county council. I ran as a Democrat against a Republican and at the time I was running, there had not been a Democrat on the county council in 24 years. I was also running in an environment where in 2015 and 2016, women candidates had been almost consistently defeated. In the 2015 West Lafayette city council race, three women ran and all lost, leaving a West Lafayette City Council without female representation for four years.

County council deals with issues like roads, bridges, courts, Sheriff’s office, etc. It’s the budget approval body, and that is most of its focus. I had become interested in running for office when I attended public office candidate trainings to help others. I’m a business librarian and work quite a bit with economic development and local entrepreneurs, so I understood many of the financial aspects from my work with the business community. I am also involved in critical librarianship and was feeling that I was reaching the limits of what I could do from inside of the system. Because I believe that librarianship is truly political, I believe we need to get involved in politics, where many of the decisions that can affect librarians and library partners get made.

On my college campus, I already really loved mentoring students, connecting colleagues, and was looking for ways the library could provide unique value. Campaigning is very similar. There were of course some negative interactions, but the vast majority were very positive in a powerful way for me. I knocked 2,000 doors in my district. I ran advertisements on the sides of buses. I attended neighborhood meetings, fish fries, county fairs, Halloween parties, fall picnics. It sounds scary to put it all together in a list like that, but each of these in itself was less difficult than trying to plan a summer reading program or get a group of cross-campus partners to agree on a logo.

There were many positive effects of my run. First, as a millennial, I helped show the viability of millennial candidates in my town. Second, I was a successful woman candidate who beat a male candidate that year. And lastly, and perhaps, most importantly, I think it meant something to run as a librarian. Every time I talked about running for office as a librarian to other librarians, it blew their minds. Like many, they had never considered how their skill set would fit into being a local elected official.

I also like to think, in my daily conversations and exchanges as an elected official, that I help to reform people’s ideas about what librarians do. People without recent interaction with libraries envision librarians as some of book hoarder and don’t realize we do other things in the community. I’ve been able for these people to update their perceptions of the position and the role of the library in the community. When we talk about making government transparent, librarians already do that. When we talk about accountability, librarians do that. When we talk about open, thoughtful public discourse: that’s where librarians need to be.

Conclusion: But what if you lose?

I was lucky to win my race for county council, but I’m very aware that things could have turned out very differently in my race. About double the amount of people turned out in the midterm locally in 2018 than did so in 2010. I was lucky to have the support of my family, my friends, and many allies across local government. I had many other candidates running that pushed me to work harder.

Running for office comes with risks. It involves making lots of public statements that could be misunderstood. Running for a partisan position means all your friends and neighbors are aware of your political affiliation, and might make assumptions about your beliefs. It changes the way that people see you. And it’s certainly not a fair process. People who have run amazing campaigns sometimes lose, for reasons that have nothing to do with them. Sometimes turnout is low, or people come out to vote for the other party in a different race and in doing so they vote against you without knowing anything about you.

I thought a lot about what this experience would mean if I had lost. If I lost, I would have still started a conversation with 2000 of my neighbors. I still would have shown that millennials candidates can run serious campaigns. If I had lost, I would still have started community conversations about the opioid crisis, about fiscal stewardship, and about transparency in government. I had still influenced people’s perceptions about librarian work. I would have still contributed to the coalition of people that could respond the next time. If I had lost, I still would have shown how someone who looks like me and thinks like me can still be taken seriously as a candidate. Even if I had not won, I would have made real and tangible contributions to the people and systems around me that benefit both the public and the profession.

Librarians advocate in many different ways in many spaces. They write bills, they raise funds, they talk about library value and library needs. I don’t think running for office is something for every librarian. It take a lot of time and a lot of work. But I think as a profession, it offers tremendous opportunity for us to advocate for ourselves. Libraries and librarians matter. While citizens may able to lobby elected officials in office, ultimately the real conversations happen outside the county building and in people’s homes and offices, where they weigh how they will vote in the election. We need you.

Works Cited

Correal, A. (2018, February 28). Once It Was Overdue Books. Now Librarians Fight Overdoses.

Retrieved April 29, 2019, from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/28/nyregion/librarians-opioid-heroin-overdoses.html

About the Author

Ilana Stonebraker is an Associate Professor of Libraries, Business Information Specialist at Purdue University. She represents District 1 as a member of the Tippecanoe County Council. She is a member of the Purdue Teaching Academy, a 2017 Library Journal Mover and Shaker, and a Greater Lafayette Commerce TippyConnect Top 10 under 40 Award Winner. She tweets @librarianilana .

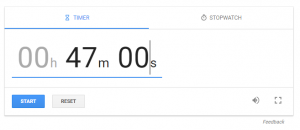

on the board. I usually google it (pictured), though I am sure that there are better ones on the internet. I do this for a couple of reasons. It helps students keep the time. That’s really important. Second it helps me keep the time. Third, everyone can see it. It’s not disputable.

on the board. I usually google it (pictured), though I am sure that there are better ones on the internet. I do this for a couple of reasons. It helps students keep the time. That’s really important. Second it helps me keep the time. Third, everyone can see it. It’s not disputable.